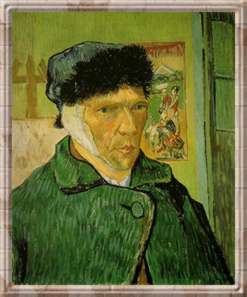

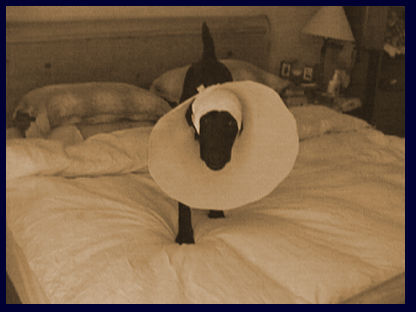

Siskogh

Portrait of the Artist

with One Ear

t

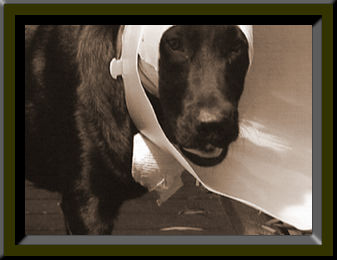

ake one spunky nine-month-old puppy. Add a foul-tempered Bad Dog with

sharp teeth and an appetite for oreille du Labrador at the local

off-leash park. What do you get?

At first, what you get is a discouraged, beaten-down dog. What you lose is a chunk of ear ... and your sense of self.

"This collar looks really, really, really stupid," writes Siskogh in one of his early journal entries. "Can't eat properly, can't lick myself intimately — what's the point of going on?" Despondent, he develops a tragic addiction to organic buffalo bones.

At his lowest ebb, Siskogh happens to glance at the television. It's tuned to TV5 France, which is running an eight-hour documentary on the history of the goofy fur hat.

But it's not the hat that catches Siskogh's imagination.

We may never know if it was a hallucination, a freak bout of television interference, or a genuine spiritual experience. But Siskogh hears the voice of Vincent Van Gogh ... speaking directly to him.

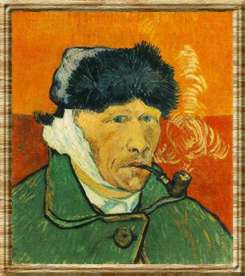

"Boy, there's nothing like a pipe to make a goofy hat look even dorkier, is there?" Van Gogh asks. "Hey, you're looking mighty low, there. You know what I do when I'm feeling depressed about no longer needing half my stereo? I paint."

The Dutch master's words come as a balm to the long-suffering canine. If Vincent can lose an entire ear — not merely have it injured — and not only paint like a champion but also get his very own Don McLean song, why not Siskogh?

He perks up instantly, and sets out to the neighbourhood art supply store to buy paint, canvas and a set of brushes specially fitted for organisms lacking opposable thumbs.

Once he returns home, he props a mirror next to his easel. He gazes at his image fiercely ... and then he dips his brush into the palette.

Forty-eight hours later, trembling with exhaustion and exhilaration, Siskogh sets his brush into the tray and stares, incredulous, at his first self-portrait.

Through the raw energy of this work, we can see both the thrill of the newfound power of creation, and the frustration Siskogh must have experienced at the inability of his nascent talent to fully translate his vision to canvas.

The controlled exuberance of this painting, which he titles I'll Give You A Nice Kiss If You Take Off This @#$#%ing Collar, captures the imagination of Vancouver's art scene. It captures $18.7 million at auction on MyBC.com.

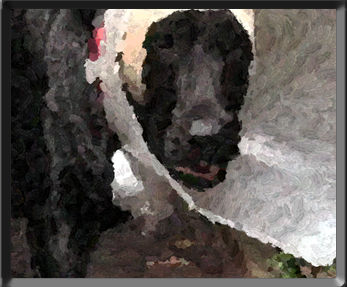

It's never easy to cope with the demands of instant fame. Siskogh, terrified that his early success was merely a fluke, retires to his bed for three weeks after selling five more canvases. Grappling with his demons, he soils the feather duvet repeatedly.

The mounting dry-cleaning bills take their toll. Broke but sympathetic, Siskogh's human roommates sit him down and force him to confront his innermost fear: that his art — a subconscious proxy for his damaged beauty — will be rejected by his dam, Ch. Guelphline Huntsdown Tulip.

A breakthrough: Siskogh's therapist makes a call to Guelphline, and arranges for Siskogh to talk to Tulip for the first time since their separation seven and a half months previously (the result of a profound disagreement over the fundamental nature of kibble).

Inspired, Siskogh puts brush to canvas as soon as he hangs up. The result: I Can't Help But Notice That I Still Have This Damn Thing On, his most famous and lasting contribution to Vancouver's canine art movement, known informally as the Obedience School.